Human Rights Commissioner Galen Kirkland

(Photo: Thomas Good / NLN)

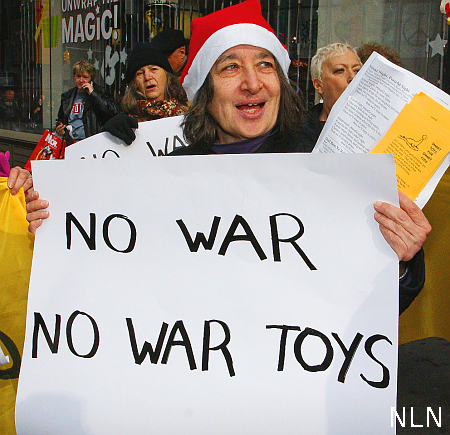

STATEN ISLAND, N.Y. — When asked what he thought of western civilization, Mohatma Gandhi famously quipped, “I think it would be a good idea.” New York State Human Rights Commissioner Galen Kirkland agrees.

On Wednesday, December 9, The Staten Island Advance sponsored the Sixth Annual Anti-Bias Summit. The summit was co-sponsored by a number of community groups, including the NAACP and the Staten Island Clergy Leadership. Project Hospitality organized the event, which took place at the Albanian Islamic Cultural Center, a mosque on Staten Island’s North Shore.

Imam Tahir Kukiai opened the proceedings, offering a prayer for blessings on those who had, “[..] Gathered to implement one of God’s teachings: justice, mercy and peace amongst his creatures.”

The NAACP’s Ed Josey, President of the Staten Island Branch, told the crowd, “We need to create a community that cares proactively — not just communities that respond when things go bad.”

After recognizing the representatives of local elected officials — Bill Tate from Rep. McMahon’s office, Tom Aiello from Governor Paterson’s office, Chris Bowers from Assemblyman Matt Titone’s office, Angelo Thornton from Council Member James Oddo’s office and Chris Johnson from Council Member-elect Debi Rose’s office — Josey introduced attorney Galen Kirkland, the keynote speaker.

Ed Josey of the NAACP

(Photo: Thomas Good / NLN)

In May of 2008, Galen Kirkland was appointed by Governor David Paterson to the post of Commissioner of the Division of Human Rights. At the time, Kirkland was working as the Assistant Attorney General, Civil Rights Bureau at the New York State Office of the Attorney General. Prior to working at the OAG, Kirkland was the Executive Director of Advocates for Children of New York, overseeing educational advocacy programs in the New York City public school system. From 1989 to 1990 Mr. Kirkland was the Executive Director of the New York City Civil Rights Coalition, a coalition of civil rights, religious, and community organizations. In this capacity, Kirkland responded to bias-related violence and organized multiracial coalitions in various neighborhoods to prevent violence.

Kirkland is charismatic, articulate and possessed of unflinching resolve. Taking the podium, he immediately set the tone of his remarks by noting that the subtitle of the event — “from tolerance to trust” — should be changed to “from acceptance to trust.” Kirkland told the sympathetic crowd that, “Tolerance is still a very negative frame of mind, it’s a closed heart.”

Kirkland looks and sounds the part of the civil rights old-fighter. He grew up in Harlem, raised by a single mother. His mother, who will be 92 in February, instilled in him a passion to be a part of the fight for social justice. Coming of age in the Sixties, Kirkland heard Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. speak and came away inspired. Seeing civil rights activists beaten and sprayed with water cannons, Kirkland felt confused. Struggling to understand why southern whites hated African-Americans, young Kirkland read whatever he could get his hands on.

Galen Kirkland

(Photo: Thomas Good / NLN)

“I read a book by a woman, a Polish woman, who had survived the Holocaust in Europe and her account of the absolute absence of compassion in the Nazis and their total cruelty was horrifying. But what it did was to help me as a child understand that the same mass insanity that was empowering Europe at the time was what was operative here in the United States and it helped me understand what was going on. Once I understood that I realized that I wanted to become a lawyer and fight for social justice,” Kirkland said.

In the 1986 Howard Beach incident, a mob of whites attacked four young black men. The mob chased a badly beaten Michael Griffith onto a highway where he was struck by a car and killed. Reflecting on the incident, Kirkland came to the conclusion that silence in the face of bigotry produced a “degradation of our humanity” — people of conscience must act. But how?

“The basic question that confronts us is how we overcome the most repressive, violent, bigoted instincts that some people have,” he said.

The answer to Kirkland’s question resides in a sense of community.

Noticing that many people are willing to stand up for decency and justice “as long as they have somebody to lock hands with,” Kirkland said that “Organizing to overcome the ignorance of people who don’t want to accept others who are different from them requires really hard organizing: person to person, in small groups, on a sustained basis, innovative thinking and dedication.”

But it requires something else that Kirkland said he was never taught in law school.

“There also has to be love in your heart,” he said.

“And here we are, in the Albanian Islamic Cultural Center, meeting while the United States is at war in Iraq and Afghanistan. At a time when many people feel as if they’re free to vent aggression and hatred towards Muslims because of the fact that radical jihadists have attempted to sieze the mantle of Islam. But the fact of the matter is, we are all under a responsibility to defend the rights of Muslims in this country, in this city, in this state,” Kirkland said.

“If we don’t defend our Muslim brothers and sisters we are all diminished because our human rights are interdependent,” he added.

Recalling the Buddhist concept of interbeing — and Martin Luther King, Jr’s “beloved community,” Kirkland appealed to the young people in the mosque to pick up the mantle of nonviolent activism in the name of peace and social justice.

As someone who practices what he preaches, Kirkland invited a former Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee field secretary to address the NY State Division of Human Rights. Shortly after he was appointed to his current post at the Division, Kirkland asked Bob Moses, who worked in Mississippi in 1964 — during the Freedom Summer voter registration drive — to visit New York. Moses, one of SNCC’s most influential organizers back in the day, told the Division’s staff that “The civil rights movement [ of the Sixties ] stopped short.” Moses argued that the movement failed to address the issue of education. Moses said that today, African-Americans receive a “sharecropper education” — and he called for a second civil rights movement. According to Kirkland, Moses electrified the Human Rights Division staffers. He was so impressive that the Division asked him back a second time. And he came.

A recipient of the War Resisters League Peace award in 1997, Bob — now “Robert P.” — Moses teaches trigonometry at Lanier High School in Jackson, Mississippi and is working to pass a constitutional amendment that states that “every child in this country is a child of this country and is entitled to a quality public school education.”

Inspired by Moses and other Sixties-era activists, Kirkland continues to work diligently for civil rights and social justice. And he urges others to do the same. Kirkland told the crowd at the mosque that to organize a community to respect human rights, “You reach out to the good people and you never stop reaching out. And you never stop meeting. And you never stop discussing. You keep fighting, day after day after day.”

Although he was heartened by the number of young people who attended the summit, Kirkland realizes that full enfranchisement of all who live in the U.S. is a long way off.

“Some people say we’re civilized. I say, we’ve made a lot of progress but we’re not there yet,” he said.

View Kirkland’s Speech In Its Entirety

(Photo: Thomas Good / NLN)

View Photos/Videos From The Event…